Do as Dorothy did: Noticing, being, feeling, pacing (Dungeon Ghyll)

Aim

To ‘be’ in place, without focusing on doing anything in particular, or achieving anything in particular. This experiment encourages you to notice what is around you that you might normally rush past on your way to a destination or to reach a certain point. It is an exercise in listening to your body and its needs, in relationship to the wider world. It asks you to stop along the way, to pause, to reassess your surroundings, to notice what others don’t simply by being yourself, in place, drawing on pacing techniques used to manage pain and other physical symptoms. It is an exercise in companionship with place and with the more-than-human world; in recognising your own body as part of a wider eco-system (or perhaps on this occasion this should read ‘weather-system’…all of the images shown here were taken on one rather changeable autumn day!)

This route has been developed in collaboration with Polly Atkin. Polly’s debut collection of poetry Basic Nest Architecture was published in February 2017 by Seren, which was followed in October 2021 by her second collection Much With Body, supported by a 2020 Northern Writers Award. Her first nonfiction book, Recovering Dorothy: The Hidden Life of Dorothy Wordsworth, which explores Dorothy’s later life and disability, comes out with Saraband in November 2021. She has also written a hybrid memoir exploring place, belonging and chronic illness, supported by the second year of the Penguin Random House WriteNow scheme.

Background

Most of the background text for the Scree experiments have been written by myself, in conversation with the collaborating writer. The personal nature of this experiment makes it fitting that what follows is in Polly’s own words:

“This route is informed by my own experience of being a disabled walker with balance-issues and a tendency to fall over and into things. I spend a lot of time when I’m walking looking down at my feet to check where I’m putting them. Between this, and balancing fatigue, energy-limitation, and pain, I’m slow and ponderous. I rarely take walks in places I don’t know, because I can’t be certain of the ground or the distance, or that I will have enough energy to find my way back to where I began. Living with an energy-limiting chronic illness means you are in a continual process of weighing up the energy you will spend on a particular activity, versus the effects of the activity on body and mind (positive or negative), versus the absolute necessity of it. Disability requires planning at a level of which able-bodied walkers rarely have any concept. Because I’m ambulatory, I don’t have to check whether routes are really wheelchair accessible when they say they are, or whether there is enough disabled parking to allow me to get a chair out of my car, and all the complex things that are part of daily existence for wheelchair users. Because my conditions affect all of the systems of my body, I do however have to think about whether there is a toilet nearby (because I can guarantee I will need it), about whether I can carry enough water with me (because I can’t carry very much of anything at all but I need to drink a lot), and whether there is phone signal in case I fall and injure myself or need help.

My main aim on any walk is to use as little energy as possible, whilst having encounters with the more-than-human world that will enrich my day. As Kate Davies and Eli Clare have both written of beautifully, though, disabled walking has compensations of which able-bodied walkers rarely have any concept. Similarly, Josie George, who uses a wheelchair outside the home, writes of ‘bimbling’ as a practice, centred on ‘not going anywhere’, and on observing the small and local. When I am walking, I take frequent breaks to rest, stop, catch up with myself, using a technique called ‘pacing’ which is often taught in illness management. The aim of pacing is never to get to the point where you are too tired or in too much pain, but to stop and rest or change position before that happens. This can be hard to get your head around if you’re used to pushing through everything or if, like me, you’re always tired to begin with. When I began to understand pacing, and put it into practice, it changed my relationship with activity and with my own body. It also changed my relationship with the nonhuman. Natasha Lipman has a great blog on pacing if it’s not something you’re familiar with but you want to learn more.

Over the years, I’ve realised that when I pace myself on a walk, I notice things that other people on the same paths don’t. People will walk past me, run past, cycle past, and not notice the red squirrel I am watching in the tree over our heads, or the dipper in the stream at our feet, or the wagtail on the fence, or the owl sleeping in the hedge. I’m also more alert to weather changes and changes in the texture of the ground than many able-bodied people, because I feel them keenly in my body. I don’t have the option to not notice things that pass many people by, but because of it, I often have a more intense experience with a place than others. For me, the most productive thing to do is nothing. Just to be, and observe what else is being around me.

In ecopoetry, walking is frequently presented as both analogous to the human condition, and to the writing process. Walking is treated as both essential field work, and as a neutral, easy activity which anyone can join in with. It is never presupposed that a writer may not be able to walk at all, or may only be able to walk accompanied by pain, loss and risk. The naturalization of this link shuts out writers who can’t walk, or for whom walking is far from a benign regenerative activity. But there are many other ways to think creatively outdoors, that don’t include walking. One of my favourite bits of Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere Journal, which I think about a lot is an episode where she and her brother William lie on the ground – in a trench, or hollow, really – in a favourite wood, and just soak up the world. It’s April 29th 1802, and on that day Dorothy sits and listens and watches in three different places – in the wood, on the ground in the wood, and on grass under a wall. Each time this kind of quiet slow observation expands what she notices:

We then went to Johns Grove, sate a while at first. Afterwards William lay, & I lay in the trench under the fence—he with his eyes shut & listening to the waterfalls & the Birds. There was no one waterfall above another—it was a sound of waters in the air—the voice of the air. William heard me breathing & rustling now & then but we both lay still, & unseen by one another—he thought that it would be as sweet thus to lie so in the grave, to hear the peaceful sounds of the earth & just to know that ones dear friends were near. The Lake was still there was a Boat out. Silver how reflected with delicate purple & yellowish hues as I have seen Spar—Lambs on the island & Running races together by the half dozen in the round field near us. The copses greenish, hawthorn green.—Came home to dinner then went to Mr Simpson. We rested a long time under a wall. Sheep & lambs were in the field—cottages smoking. As I lay down on the grass, I observed the glittering silver line on the ridges of the Backs of the sheep, owing to their situation respecting the Sun—which made them look beautiful but with something of strangeness, like animals of another kind—as if belonging to a more splendid world.

This route is asking you to do what Dorothy did – to rest in a place, to quietly observe your surroundings and yourself. To pace yourself. You are not separate from the place you are in. How you feel, in your mind and your body, is just as important as what it outside your body. Notice it all.

Route instructions

Click on the image above to open an interactive version of the map on Outdoor Active. Otherwise you can download the GPX file of my route here (© OpenStreetMap contributors)

Route: Easy (2.8 miles, 175 feet of ascent)

Starting point: the National Trust car park by the Sticklebarn / New Dungeon Ghyll hotel.

Due to the aims of this experiment, it was important to ensure that the route was fully accessible. The first half of the route, heading east from the New Dungeon Ghyll, follows a fully accessible track (following the route of Miles Without Stiles 43).

The second half of the route is not fully accessible - those in wheelchairs will need to turn around at the bridge and go back the way you’ve come - but provides some variety for those who are able. It’s not a long route, but this fits with the aims of not getting anywhere in particular, and appreciating your surroundings as you go. The slower you take this route (the more you sit down along the way and think, or rest) the better. And as the accompanying images for this experiment illustrate, it’s really not essential to head out into the high fells to get some great views!

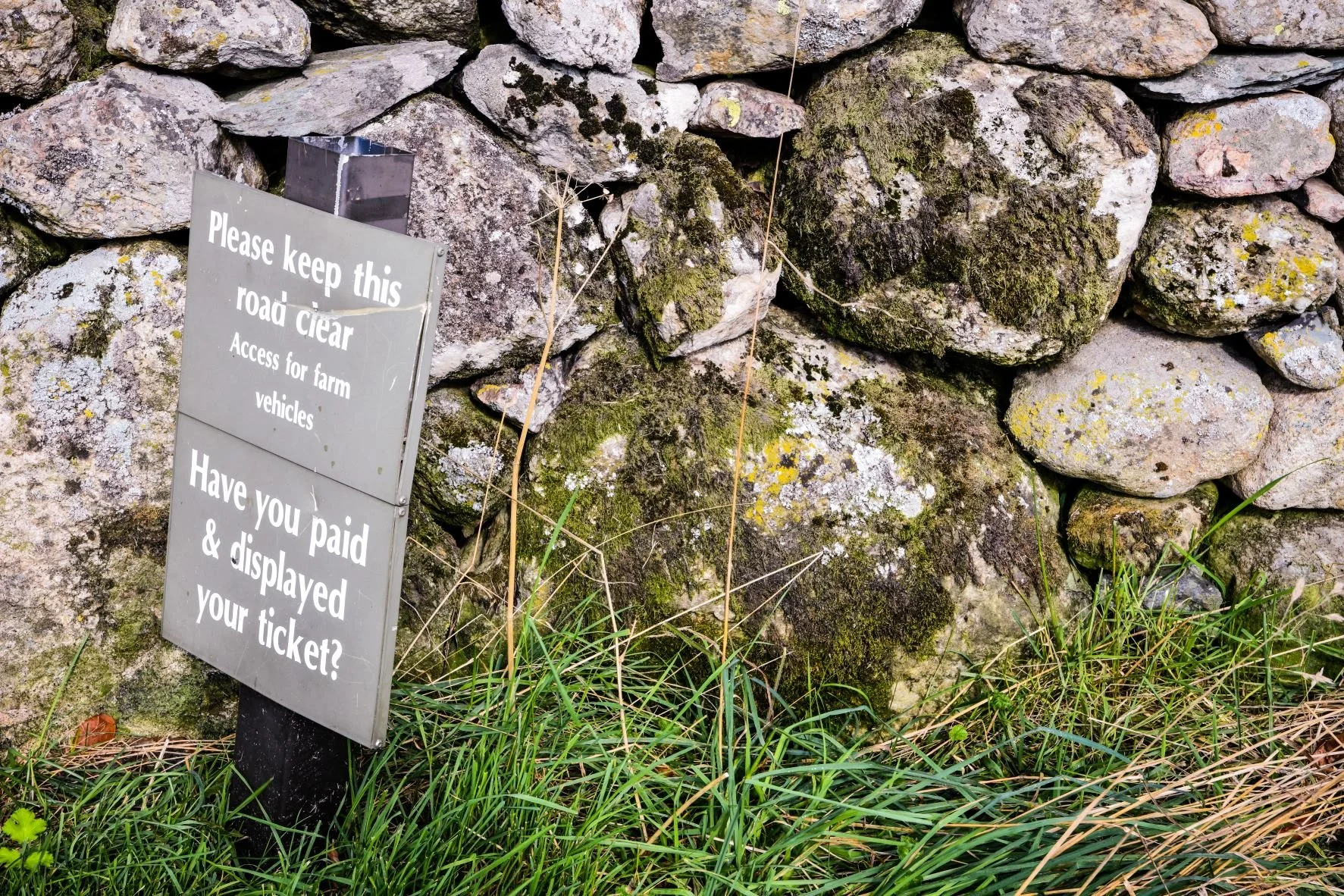

Writing & Visual Art Ideas, & Virtual Alternatives

1. En route, you may notice things that other people (intent on ‘doing’ the Langdale Pikes for example) might not. They can be small, like a beetle, or vast and ephemeral, like the way the light shifts, or the wind on your face. Use all the senses available to you, and take notes / sketch / photograph what you notice. Stop frequently, and (crucially) take your time. A good first place to stop is by the wall along the beck just a few metres along the path, to watch the water and the trees. What if you face up to the sky, and the fell tops, what if you face down to the ground? What if you look out at the fields? How does your body feel? What you do notice in yourself? Do you meet other people on your route? Do you talk to them? If you do, do they alter what you notice around you? Each time you stop and notice what is around you, you might like to choose one particular thing to focus on. Describe / sketch / photograph the thing, and where it rests in place. What does it notice about what is around it? Does it notice you? If you approach the road, what do you notice? Can you hear traffic? Other people? What’s different? How does the tarmac feel under you rather than the stony path? Does it make a different noise when you walk or roll on it?

2. Also note down any thoughts which pass through your mind, without getting too drawn into them. Just note them down as is, and then let them be in your notepad. Do this whether you are responding in writing or visually. These notes might prove useful when it comes to re-working your visual art when you get back home.

3. Feel free to make any diversions or digressions that the moment suggests to you (such as to some prehistoric boulders just off-route). Try and notice the instincts and feelings which lead you off route, and try and record these in words or images. If you do divert to the boulders (for example), have a good look at them. Sit with them, and just soak up your surroundings. Think about how they sit in the field, with the tree – much younger than them – growing through them. If you can get close enough to see the ring and cup marks, what do you notice about them? Can you imagine the hands that made them, thousands of years ago? No one knows why people made these carvings or what they mean, although there are many theories. What do they mean to you? What could the cup and the ring stand for? Do they remind you of other things, shapes, geographies?

4. There may be various other ‘features’ en route where you wish to spend a bit more time and focus. You might notice their location, context, where your imagination leads you, what memories are provoked.

5. When you reach the bridge over the beck, pause on the bridge, if you can, or on the shore on the far side. Listen to the sound of the beck. How full is it? Do you see anything living along its banks or in the water? Spend time on the bank, taking in the surroundings. Make notes or sketches, or photograph things you notice that appeal or stand out to you.

6. If you follow the simple route and go out and back along the same path, what do you notice differently going in the opposite direction? How does it feel to retrace the same route? Is it frustrating, satisfying? Boring? Include your feelings in what you notice, and how your body feels.

7. Back home, draw together your notes, photographs, thoughts and sketches into some written or visual art, without trying to interpret the experience too much. Let it be, and see what comes, and allow space for artistic surprises as you go!

Route adaptations for walk-from-home

This route is infinitely adaptable to any walk, anywhere. Just make sure to remember to keep it short and straightforward so that you can focus on the aims of the exercise, not the physical challenge or route-finding!

Polly’s poetry

Doing as Dorothy did

Start with sparrows

bathing in a carpark puddle,

brown on brown

stumble forward into

cloud shift, leaf rustle, the crackle of sun

moving across the fossils of glaciers

rush of water in the rain-laden beck –

how long can you watch the long green manes

of the kelpies as they gallop through the river before

you fall for their glitter? Don’t stare so if

you don’t want to test it.

The path here is wide and certain,.

Puddles open portals from the ground to the tops

when the wind is in the right direction. You could step

right into them, never come back.

One of us wants to be high on a ridge,

safe in the nest of the sky. One of us

wants to doze on a sun-warmed boulder

and dream the body as debris, scars

as art, as proof of culture. Together

we are tumbled down the old road of the valley till the weather

wears us smooth, precious.

The first thing that stopped us: jackdaws all rising

at once from a line of oaks, in dark

scudding clouds, stirred round the valley like the valley

was a saucer and they were the tea leaves, making fortunes

of themselves though I could not read them. I forgot

murmurating jackdaws call in rain.

A sparrowhawk drew a sharp line below them.

There was something in this, in the pheasants calling,

in the two grey squirrels and their chase, in the climbers

in their matching uniforms, clustered round crags

in the way it was all precision cut

by the sun. Until it was all undone

by the downpour, and all that was left was the breathing

body and freezing water. Numbness

and pain. What I remembered then –

the absence of rain speaks too – is a kind

of sound, overwhelming as a storm in its way.

We can never out walk ourselves.

Lucy’s poetry

The principle of walking circles

To always finish

at the place

where you began.

And begin, again.

I feel the magnetic

variation of the mountains

at the base of my spine.

Sending my inner compass

spinning, and the puddles

curdling with rain.

I jump an undercurve of rainbow

whipping like a skipping rope

beneath my feet.

I wear the shifting weather

in different stitches of rain.

My spinal cord is as red and raw

as an inner branch of bramble.

I envy the river, pushing back against

itself, and fear the mutilated bird

which is strewn through undergrowth

more than the long-gone bird of prey.

No matter how you try.

You’ll never not outlive the weather.

The approaching rain a darker

shade of green…

So the southern aspects of the trees

are turning. A squirrel skips along

the knife-edge of a dry-stone dyke.

A teenage herdwick shakes its fleece

dry, like a domesticated dog.

I’m walking slower than the changing

seasons, seeking order in things.

Fence post. Mutilated tree stump. Tree.

It surprises me to be surprised

by the rasping call of pheasants.

I find the levelling of the landscape

flattening me. I associate with the

larger-than-life under-shadow of leaves.

Between so many boundaries.

The drystone dykes, the fence lines.

Barbed wire. Hedges. Paths and rocks

and trees. The reflection in the river

holds the place where earth meets sky

and I –

As the clock strikes 5, I sense

an overwhelming silence.

A loss of wind. A darkening sky.

The air weighs heavy on my shoulders.

A signpost points the way to Dungeon Ghyll.

Back towards the place I started.

Back towards the illusive chance to start again.

Lucy’s photography

For me, the processes of pacing and slowing down, and most especially noticing, are qualities of a walk which in my own experience are enhanced by carrying a camera around my neck. An audience member asked me during the Scree launch whether my camera created distance between me and the landscape; on the contrary, carrying a camera (combined with my love of macro work) encourages me to participate in the landscape in a far more attentive way than I do without it… I don’t have a specific gallery which relates to this experiment - the images with which I’ve illustrated this experiment are witness to what I saw, observed, and in which I took part. Incidentally, all of these images were taken over the duration of one mightily changeable autumn day. Views of Harrison Stickle dominated the route, as shown in the range of moods in which it’s presented here. The below image signalled more changeable weather on its way, and was taken during my drive home.